- Home

- Susan I. Spieth

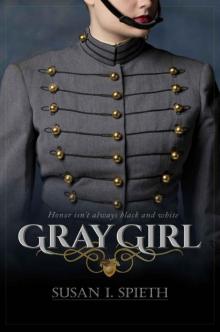

Gray Girl

Gray Girl Read online

Gray Girl

Susan I. Spieth

Gray Girl is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or events is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 2013 Susan I. Spieth

All rights reserved. ISBN-13: 978-1491272817

[email protected]

DEDICATION

To my mother and father, you are my foundation. To the women of West Point, you are my kindred sisters. To my daughters, you are my best work. To Bob, you are my best decision. To my Creator, Redeemer and Sustainer, You Are.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am deeply grateful to many who helped Gray Girl come into existence. Thank you, Lucian Truscott, for reading the first few chapters and advising me to start over. Lisa Bruck, thank you for reading the first draft and pretending to like it. Your feedback during our walks prompted the genesis of a better story. Thank you, David Bullock, Liz Horner Boquet and Luci Fernandez (a West Point roommate), for reading sections and encouraging me to keep going. Barb Eimer, thank you for editing the fourth or fifth version and giving me renewed hope after I had shelved Gray Girl for six months. Thank you, Jenni Moehringer (’85) and Marcia Ganoe (’84) for your encouragement. Linda Fiebig, thank you for editing what I thought was the final draft until you got your hands on it. Special thanks to my cuz, Chris Zarza, for a phenomenal cover design. Twice.

Thank you, Alex and Marlo, for many things but mainly for always asking, “When can we read it?” You can read it now. Finally, thank you, Bob. Your willingness to read each version (which isn’t fair to ask of anyone), your gentle feedback, your persistent encouragement, and your patience with me (no easy task) are just a few reasons why I love you beyond words.

1

“A cadet will not lie, cheat or steal, nor tolerate those who do.”

Cadet Honor Code, United States Corps of Cadets, United States Military Academy at West Point, NY

Thursday, May 6, 1982

1530 hours

She felt the warm tickle begin between her shoulder blades, then glide slowly but purposefully down her spine, curling inward at the small of her back until coming to a halt at the crack of her bum. The drop of sweat stood there, like a sentry, under her Dress Gray, under the Army-issued white T-shirt, under the black webbed belt, under the heavy wool trousers, and under the Cadet Store cotton panties..

Jan Wishart stood at attention in a windowless room in front of a phalanx of thirteen young men armed not with spears but with an exacting and rigid Honor Code. Two freshmen, two sophomores, four juniors and five seniors sat across from her at three rectangular tables arranged end to end in a line. Only this was West Point, so they were called plebes, yearlings, cows and firsties, respectively. The image of da Vinci’s Last Supper popped into her head. Two Army officers occupied another table to the left looking like courtroom deputies. Their hunter green uniforms looked downright bright and cheery compared to the dark gray wool uniforms of the cadets. Yellow legal pads and pencils waited in front of each cadet, but the bulging manila folder in front of Cadet Casey Conrad bothered Jan the most. She knew it contained all the evidence and statements against her—most of which she had not seen. She had been notified of the charges only three days ago.

Conrad, the Brigade Honor Captain, pulled a paper from the pregnant file and delivered the prepared statement to all present. “Cadet Wishart, you have been charged with two Honor Code violations regarding events on May second and third. The responsibility of this Honor Board will be to weigh the evidence and testimony and determine whether or not the Code has been breached. If we determine guilt, we will recommend your immediate dismissal from the Corps of Cadets to the Superintendent of the United States Military Academy. If we find innocence on all charges, then you will return to your company in good standing.”

Without moving her head, she glanced toward her Army legal counsel whom she had met only ten minutes before reporting to this room. Major Hastings sat to her right looking down at his shoes. Jan lifted her eyes, looking for something, anything, that might help calm her stomach. Then she noticed the middle-aged, civilian woman sitting erect in front of what looked like a large adding machine. Something about her straight back made Jan feel slightly better.

“Do you fully understand the charges against you?” Conrad asked.

“Yes, Sir,” Jan said, shaking. How am I ever going to survive this?

She had survived quite a lot already. Plebe year at West Point is all about making it through each day, putting one Etonic sneaker in front of the other, memorizing one menu at a time, cutting one Martha Washington sheet cake and passing it up the table before being told you are a “failure to the entire Corps of Cadets” for butchering the dessert. Every day of plebe year begins at o’dark-thirty when Beanheads (plebes) deliver mail and laundry to the sleeping upperclassmen. Before breakfast, fourth classmen (plebes) must memorize enormous amounts of information—the entire front page of The New York Times, the menus for every meal, various speeches, heritage, trivia and the number of days left before the high and holy days of cadet life.

This last requirement actually serves as a small help to plebes. When you fall exhausted into the rack at Taps each night, you subtract one more day from the seeming eternity until the Army-Navy game, Christmas leave, spring break and the highest of all holy days—graduation. This small, daily discipline actually instills hope in the breast of all plebes, reminding them that if they just endure, it will eventually end. One day, this shit will all be over.

“Have you received a copy of the evidence including Cadet Jackson’s statement, the exhibits, and other statements from Cadets McCarron and Trane?”

“Yes, Sir.”

“Sit down, Miss Wishart,” the Brigade Honor Captain instructed.

Jan sat in the wooden chair at attention as required during meals in the Mess Hall—keeping her back straight, one fist distance from the chair and the same distance from the table. She squeezed her legs tightly together at a perfect ninety-degree angle from her knees.

Conrad continued, “Although I will preside over these proceedings, I have no vote. To my left are the First and Second Regimental Honor Captains, followed by their Honor Lieutenants and two cadets from each regiment.” West Point consisted of four regiments, each with approximately one thousand cadets. “On my right are the Honor Captains from Third and Fourth Regiments, their Honor Lieutenants, and two cadets from each regiment. These cadets constitute the jury of your peers to hear and decide the charges before us today.”

Jury of my peers? Only two plebes? No women?

“Now, Cadet Wishart, before we bring in the first witness, do you have any questions?” Conrad had to be at least six feet tall. All Brigade leaders were tall and usually white men. His class ring, a big, black onyx enveloping a half-carat diamond, set in eighteen-carat gold, weighed down his right hand. Firsties, or senior year cadets, now had their class rings, wearing them with their class crest facing the left. When they graduate, they will wear their rings the other way—with the academy crest closest to their hearts.

“Yes, Sir.” She cleared her throat.

“What is it then?” he asked as he looked at his notes.

“Sir, I haven’t seen a statement from Cadet Dogety in my file.”

Without looking up, Conrad said, “Cadet Dogety doesn’t wish to make a statement.”

Dogety was Jan’s Squad Leader during the first seven weeks at West Point, appropriately called “Beast,” and her current Executive Officer. He could provide a statement in her favor, but he would not go against his classmate. Cadet Jackson and Cadet Dogety were also best friends since their first day of plebe year, known as R-Day. �

��Sir, he was a witness to the events.”

Conrad flicked his wrist. “Cadet Dogety was not even present for the second honor charge. And he has the right to refuse to make a statement.”

“Sir, Cadet Dogety was entirely involved in Sunday night’s events and he has information about Monday morning that needs to be part of the record.” Jan felt like a whining child, but she had to try.

Conrad sighed. “Cadet Dogety’s actions regarding the incident have been admitted by Cadet Jackson. No one has tried to hide the fact that they were unduly hazing you. So I am not sure what more Cadet Dogety can add to the file that has not already been accounted for.”

I’m taking one last shot at this. She looked back at Conrad. “Sir, Cadet Dogety knows more about the situation that has not been mentioned in any other statements so far. He has information that will help my defense and I would like for him to submit a statement.”

“Well, Cadet Wishart, he has the right to refuse because he was not the one who brought the charges against you. You can still call him as a witness and you will be able to question him at that point.” Conrad continued to shuffle some papers, never looking at Jan.

Not every battle is Armageddon. Save your strength for later. “Yes, Sir,” she sighed.

Cadet Conrad motioned to one of the plebes who quickly rose and left the room. He returned a moment later with Jackson in tow, leading him to a small table to Jan’s right. The plebe went back to his seat while Jackson remained standing.

“Cadet Jackson, please raise your right hand and repeat after me.” Conrad read from a paper, “I, state your full name.”

“I, Markus William Jackson,” his voice was clear, strong and confident.

“Do solemnly swear to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth….” Jackson repeated every word from Conrad.

“…in accordance with the Uniform Code of Military Justice…”

“…and the Honor Code of the United States Corps of Cadets,”

“So help me God.” Jackson emphasized the last word as though his left hand had been on the Bible. He sat down in the chair, placing his gray hat on the table.

“Markus, you have charged Cadet Wishart with two honor violations. These are serious offenses. Before we begin, I must ask you if you wish to withdraw your accusations against Miss Wishart?”

“No, I stand by my statement,” Jackson said.

“We have your written account, but please explain the circumstances leading up to the honor violations in question.”

Jackson took a deep breath and began recounting his version of events. “On Sunday, May second, Cadet Dogety and I returned from weekend leave. We took a trip with Cadet Forthmeyer. Because Forthy was the designated driver, the Dogs and I had a few drinks. I make no excuses for our behavior when we returned to the barracks. We shouldn’t have made Cadet Wishart run our errands that evening, and for that, I sincerely apologize.”

Jan rolled her eyes. Asshole!

“However, our actions in no way justify the lies that Miss Wishart perpetrated as a result.” He looked straight at Jan.

Self-righteous asshole!

“Please tell us exactly what transpired when you returned to Post,” Conrad said.

“Cadet Dogety sent Cadet Wishart from H-3 to my room in B-1 with a routing envelope.” Each regiment consisted of nine companies, called A, B, C, D, etc. Company H-3 was H Company in the Third Regiment and B-1 was B Company in the First Regiment. Jackson continued, “It contained a message on a legal pad from Dogety. The content of the note does not have any bearing on these proceedings. Suffice it to say, the note was meant only for me to read.”

Just like the Watergate tapes were meant only for Nixon.

“Miss Wishart arrived to my room, I read the note, replied, and ordered Wishart to return the routing envelope to Dogety. We were just having fun.”

“Was this during study hours, Markus?” Conrad asked.

“It started about 1900 hours but ended after study hours began, about 2030 hours,” Jackson admitted.

Seven to eight thirty pm. Jan still converted military time into “normal” time in her head. The twenty-four hour military clock just never felt quite right.

“So, this went on for about an hour and a half?” The question came from the Third Regimental Honor Captain, Cadet Tourney.

“Yes, around that. Like I said, I am not proud of having taken up so much of Miss Wishart’s time. We should not have continued once academic hours began. However, Cadet Wishart did not step a foot into my room after 1930 hours. Cadet Dogety also did not allow Miss Wishart to enter his room once the academic bell sounded.”

Upperclassmen were not allowed in plebe rooms during study hours and vice-versa. This rule was taken seriously because it was linked to the Honor Code through plastic cards that hung inside every cadet’s room indicating their whereabouts. Cadets marked these cards either “academic,” “athletics,” “sick call,” “post,” or “leave,” whenever they left their rooms. If they went beyond the place indicated, it could be considered an honor violation.

“So, you sent Miss Wishart back to Cadet Dogety with a reply to his note?” Conrad clarified.

“Yes, then she came back again with another note from Dogety.” Jackson said. “She made one more trip after that.”

“Okay, so she made a total of three round trips from Third to First Regiments?” This came from Cadet Leavitt, First Regimental Honor Captain.

“Yes.” Cadet Jackson looked down at his hat as though he felt badly about that, but Jan knew better.

2

“It is a period in which entering civilians undergo the stressful socialization process which produces a well-disciplined, motivated class of new cadets who are prepared for acceptance into the Corps as fourth class cadets… The new cadet’s waking hours are completely controlled. Every activity is carefully supervised. Attention to detail and flawless appearance become second nature.”

Cadet Basic Training, Bugle Notes, 81, p. 71

She knew better because Markus Jackson had been her Platoon Sergeant in Cadet Basic Training or “Beast Barracks.” It began with R-day, the day that lives in infamy in every West Pointer’s heart and mind. It’s the demarcation line separating the comfortable, known world you left behind and the frenzied, haunted maze of shouting cadre you just marched into.

Jan Wishart spent the first few hours of R-Day paradoxically running around in circles while going from line to line. Her clothes and personal items were taken away in the first line. In the second line, she put on black shorts, a white T-shirt, black knee socks, and the ugly, black shoes she had to buy before R-Day. In more lines, someone measured her height and weight, then examined her backbone, limbs, ears, eyes, nose, and throat. Then in another line, she read the bottom row of letters and signaled when she heard a beep coming from enormous earphones.

She prayed there would not be a “pelvic exam” line. But thankfully, in the last medical line, they only asked if she took birth control pills. “Uh, no.” She wondered how many girls her age actually did.

In the uniform line, a short man measured her from neck to waist, from waist to feet, and around her hips and waist. He took her breast measurement last, his face even with the tape. He then handed her a package of white V-neck undershirts, one white collared, button-front shirt, and one pair of gray trousers.

She went to more lines for more uniforms and supplies which she put in two large green duffel bags. Her arms ached from the strain of carrying the two fully loaded bags, so when she approached a firstie with a red sash after waiting in yet another line, she dropped the bags on the ground.

“Did I say you could put your bags down, New Cadet?”

“No, Sir.” She picked up the bags.

“Did I tell you to pick up those bags?”

“No, Sir.” This time, the bags stayed in her sweaty hands while she glanced at his nametag. Dogety.

“New Cadet, you will not do anything unless you are told. Do

you understand?”

“Yes, Sir.”

“You will not say anything unless you are asked. Do you understand?”

“Yes, Sir.”

“You will keep your eyes straight ahead at all times, never looking around, not even at a nametag. Do you understand?”

“Yes, Sir.”

“I didn’t hear you. Do you understand?”

“YES, SIR!”

“Good. You are to report to the man in the red sash on the fourth floor of this building. He will tell you what to do next. Do you understand?”

Fourth floor? “Yes, Sir!” Jan turned to go, but Dogety stopped her again.

“New Cadet, did I dismiss you?”

“No, Sir.” This time she didn’t turn back to face him.

“You are dismissed, New Cadet.”

“Yes, Sir.”

Jan carried the heavy bags up four flights of stairs in the antique building. With its massive stone exterior and block interior, it seemed more like an old prison. God, the first floor would have been nice. She reached the fourth floor and saw the man with a red sash across the stairwell. I better not screw this up. Still she glanced at his nametag while walking straight toward him. She stopped about a foot away from Cadet Jackson, held onto her bags and didn’t say a word.

“What is your name, New Cadet?”

“Sir, my name is Jan Wishart.”

“Do you think we are friends, New Cadet?” He asked the question calmly, which caused Jan to question whether or not she might know him. “I’m waiting for an answer, Miss.”

“No, Sir.”

“That’s correct, New Cadet, we are not friends. And because we are not friends, I don’t need to know your first name. From now on you will be New Cadet Wishart. Do you understand?”

“Yes, Sir.”

“Good. I am your new Platoon Sergeant, Wishart. That means from now on you will do everything I tell you.” He lowered his voice to barely above a whisper. “You will run when I say run. You will crawl when I say crawl. You will scream when I say scream. And you will shit when I say shit. Do you understand , Miss Wishart?”

Gray Girl

Gray Girl